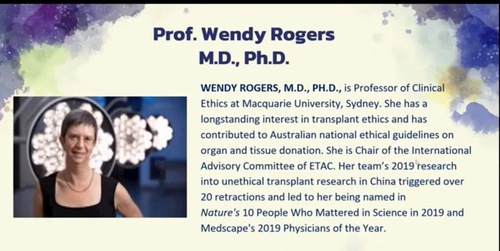

During a forum organised by the International Coalition to End Transplant Abuse in China (ETAC) on February 24, clinical ethics professor Wendy Rogers talked about the moral obligations for medical professionals to join forces and end forced organ harvesting.Rogers is a professor from Macquarie University in Australia.

In 2019, she was named one of Nature’s 10 (Ten people who mattered in science in that year).

“For two decades, controversy has swirled around the origin of some livers, hearts and kidneys used for organ transplants in China,” wrote the announcement of Nature’s 10, “Wendy Rogers, a bioethicist at Macquarie University in Sydney, Australia, found a new way to prise open the issue: examining research publications by Chinese transplant doctors. Her team’s investigation, published in February (W. Rogers et al. BMJ Open 9, e024473; 2019), triggered more than two dozen retractions of reports of transplants, after doctors couldn’t prove that donors gave consent.”

“If you think about what’s really happening, it’s unbearable,” quoting Rogers in the article.

The CCP Is Ultimately Responsible

In the ETAC forum, Rogers said the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is ultimately responsible for the forced organ harvesting because its suppression against vulnerable groups allowed the industry-scale organ transplants to happen. However, just talking about the crime is not enough and we must urge the CCP to take action and stop the crime.

Rogers agreed with the viewpoint of Sir Geoffrey Nice QC that victims of organ harvesting are human beings just like us. Similar to everyone else, they have their basic rights and need our help when their rights are violated. As fellow human beings, we are obligated to respond to their cry for help.

Professional Organisations and Individuals

There are two prerequisites for professional organisations and individuals to take action to address crimes such as forced organ harvesting, explained Rogers. The prerequisites are cognition and power. The first refers to awareness of the forced organ harvesting and the second refers to the authority of these professionals to take action against the crime. Fortunately, both of them have been met already.

First of all, professional organisations and individuals should no longer ignore this severe violation of human rights. This is a serious ethical issue with high visibility. The China Tribunal that Sir Nice chaired, for example, has conducted an independent and thorough investigation and confirmed the existence of organ harvesting in China. Its judgment has been widely distributed and broadly reported. Professionals involved in organ transplants cannot claim they are unaware of this issue.

Secondly, professional organisations and individuals could hold those human rights violators accountable. This does not mean they – or anyone else – have the power to force the CCP to do something. Rather, when professional organisations and individuals work together, they can exert huge pressure on China. People around the world can join together to tell the CCP that organ harvesting is not tolerated anywhere in this world.

Multi-pronged Approaches

There are a series of actions that may be taken to stop the crime, Rogers explained. Organ transplant practitioners can request professional societies to institutionalise and implement policies towards China. Because of their affiliation with the crime, medication professionals from China could be barred from these societies or attending conferences. These societies could also discourage members from going to China for any activities related to organ transplant.

Without these actions, if these societies continue educational and research programs with China, it would send a message that people involved in organ transplant would not be held accountable. Therefore, such collaborations and interactions with China should come to a stop.

Other measures organ transplant professionals can take include informing organ transplant patients of the danger of using organs harvested from prisoners of conscience in China. Furthermore, medical professionals could advocate for their governments to approve and implement legislatures such as “Council of Europe Convention against Trafficking in Human Organs.”

Besides educating the general public, professional societies and their members usually have many connections that could be used to audit research and education related to China. Organ transplant journals could bar publications from Chinese researchers, or exclude them from editorial boards. Clarification can be made to readers why such actions are taken.

Starting from organ transplant professional organisations and individuals, more people could stand against the crime of organ harvesting, and hold those involved accountable.

The forum on February 24 had participants from 117 organisations in 25 countries across 10 time zones. The attendees also included 12 universities, 7 news media outlets, and over 40 government officials.

“Rogers’s shift from academic to activist started at a 2015 conference that screened a documentary, Hard to Believe, discussing forced organ donations from political prisoners. Rogers had studied Australia’s transplant system, and was shocked by what was going on in China,” wrote the aforementioned article in Nature, “In 2016, she became the unpaid chair of the international advisory committee of the International Coalition to End Transplant Abuse in China (ETAC), a non-profit advocacy group in Sydney.

Following an anonymous lead, Rogers investigated a 2016 paper in Liver International, in which she found the documentation of donors lacking; the paper was retracted in 2017. Later on, more articles were retracted due to the use of data citing unclear organ sources.

All articles, graphics, and content published on Minghui.org are copyrighted. Non-commercial reproduction is allowed but requires attribution with the article title and a link to the original article.

Chinese version available

(Clearwisdom)